French silversmiths were the highest regarded craftspeople in Europe during the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries because of their rigorous training in the guild system and their innovative designs. Few examples of eighteenth-century French silver remain, however, due in large part to King Louis XIV’s 1689 decree that all silver must be melted, and due to the cost-effectiveness of having an old piece melted and recast to fit new fashions.

Rotational image of a silver coffeepot with ebony handle

created by François-Thomas Germain, 1756-57, Metropolitan Museum (33.165.1)

This coffeepot, made by François-Thomas Germain, was designed to showcase both the skill of its maker and the exciting new beverage housed inside. Coffee leaves flourish on top of the pot, on the handle, and at the spout, emphasizing the curvature of the body and the purpose of the object. François-Thomas Germain was the son of Thomas Germain, and like his father served as the royal silversmith for Louis XV, while also supplying pieces to foreign courts, notably Portugal, where six coffeepots matching this one were sent. Germain, whose name had the same sway in eighteenth-century Paris as luxury-brands do today, crafted a similarly shaped chocolate pot ten years later. The later chocolate pot, however, had a swiveling cover that hid a small hole in the lid, allowing for a long stick to evenly stir the chocolate within the pot.

The availability of new luxury goods such as coffee and cocoa necessitated new objects in which to put them, and while these wonderful examples remain, they are certainly not representative of the only form silver would have taken. For most of the eighteenth-century, silver was the main tableware used at courts, where standard services were for 36 plates. Even once porcelain replaced silver as the courtly favorite, silver was still used to line porcelain, and as a model for other media.

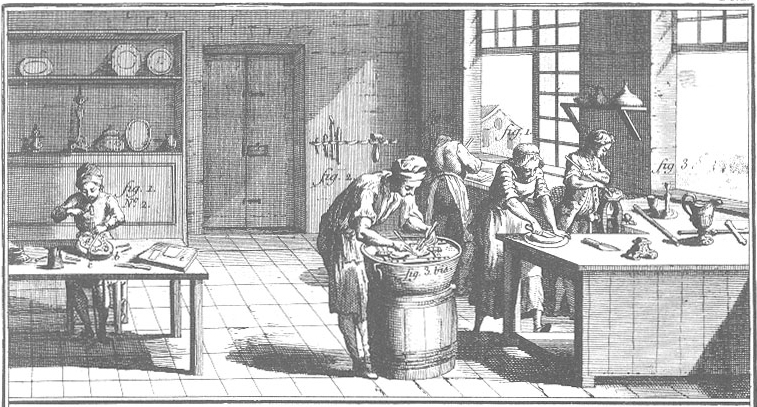

The training required to become a silversmith was rigorous. Apprenticeship was eight to ten years in length, followed by two or three years as a journeyman, and finally the construction of a “masterpiece” to be judged by the guild if a man wished to become master. The guild maintained strict quality control over the silver, and required that pieces be tested and stamped. Germain signed this piece inside the handle with his name, his position as royal sculptor, the location of his studio (in the Louvre) in Paris, and the date, 1757, which was not typical.