Interior mechanics

From the late 17th to the early 19th century, the harp underwent several phases of mechanical innovation to improve its ability to play a variety of scales and tones. Previously, the predominant type of harp was the “simple” harp, which had no mechanism of any kind. The first machine elements added to the harp were hooks placed along the right side of the harp’s neck could be turned for each string to raise its pitch a half step. This, however, had to be done manually, forcing musicians to interrupt their playing to turn the strings and sometimes resulting in accidentally played notes.

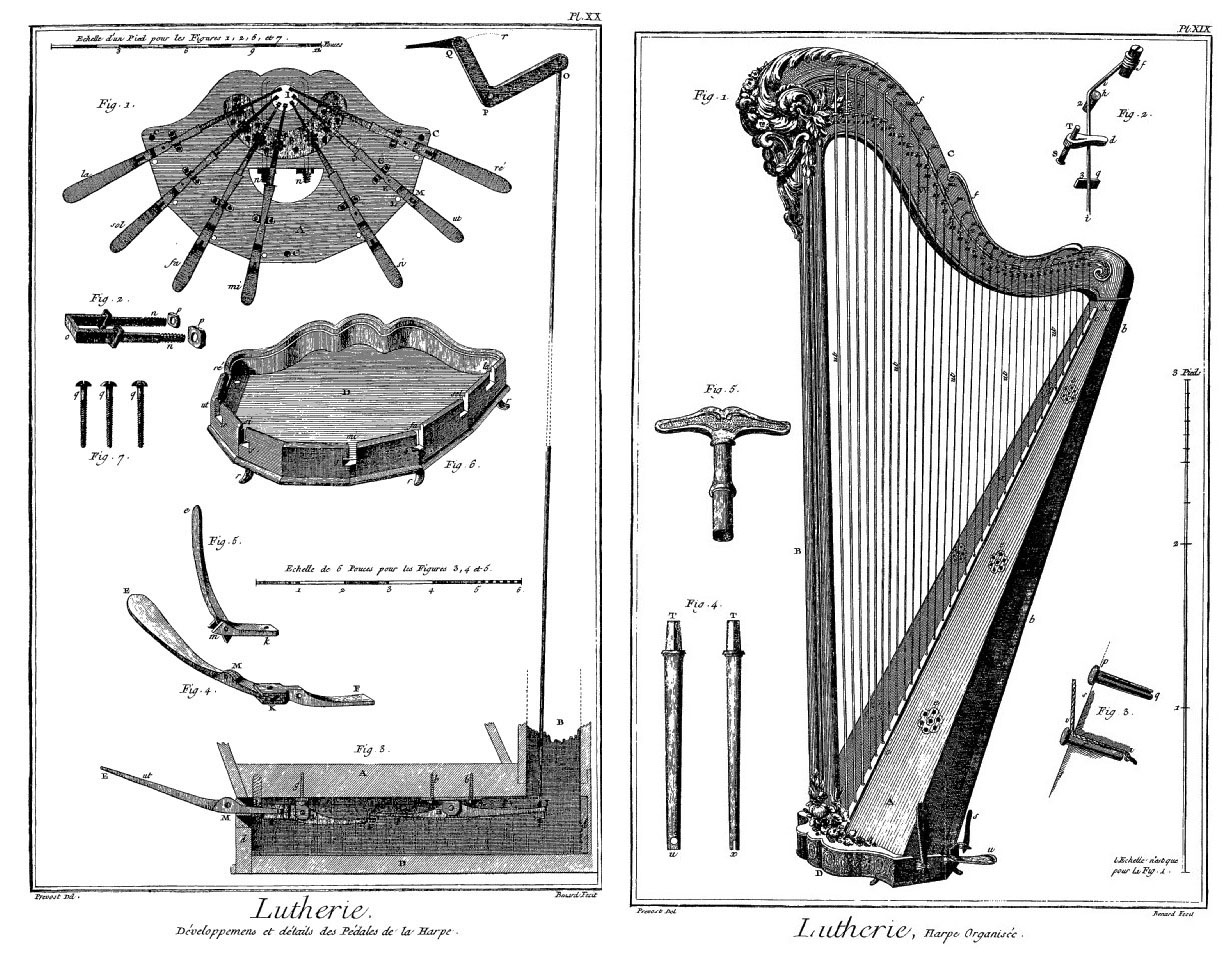

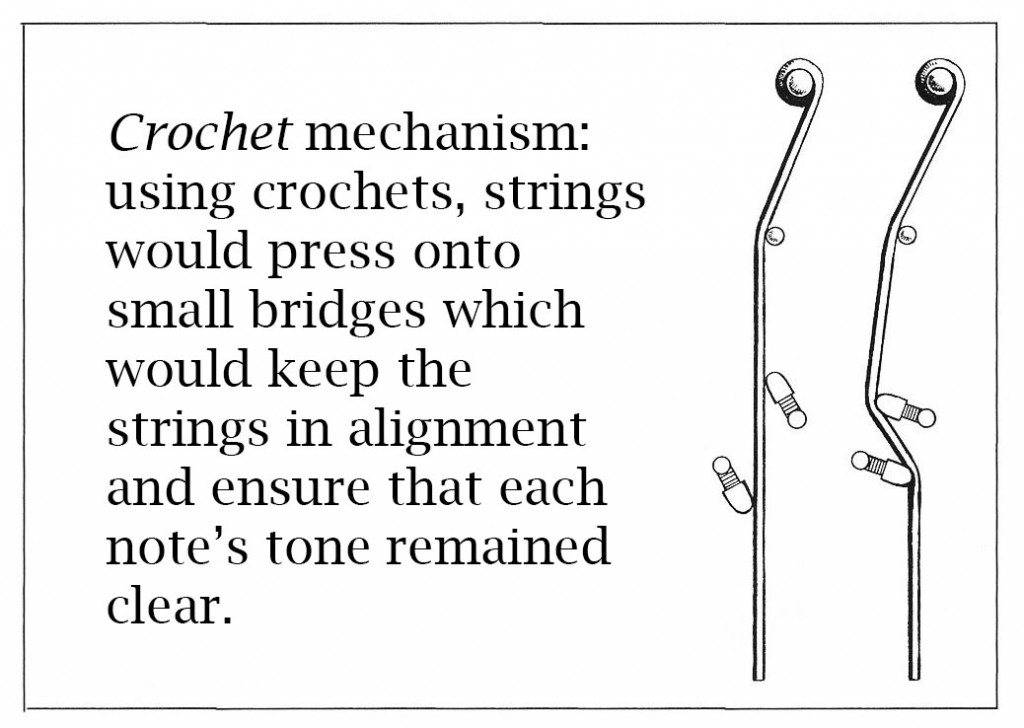

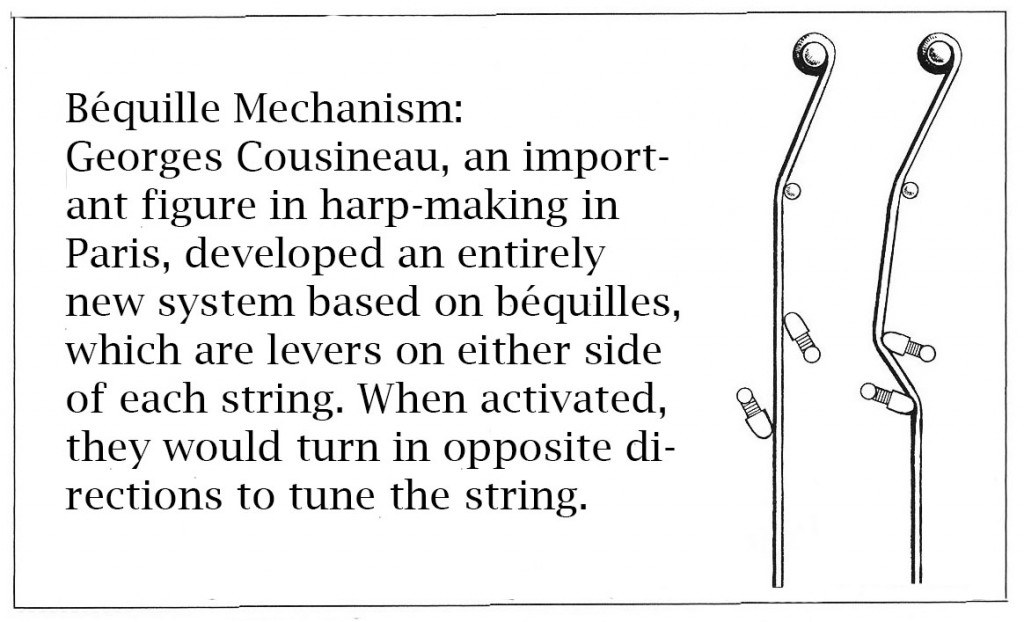

In the early 18th century, a pedal system was developed which connected the hooks to seven pedals, one for each note in the diatonic scale, at the base of the harp. These pedals allowed a player to use their feet to change the pitch of the strings without pausing or moving their fingers from the strings. French luthiers, or instrument makers, created even more sophisticated hook systems, click below to see diagrams and read about how they worked.

The luthier Cousineau also would place a brass plate with his shop’s name behind a glass plate through which some of the mechanism could be seen, revealing the mechanical movements behind the music.

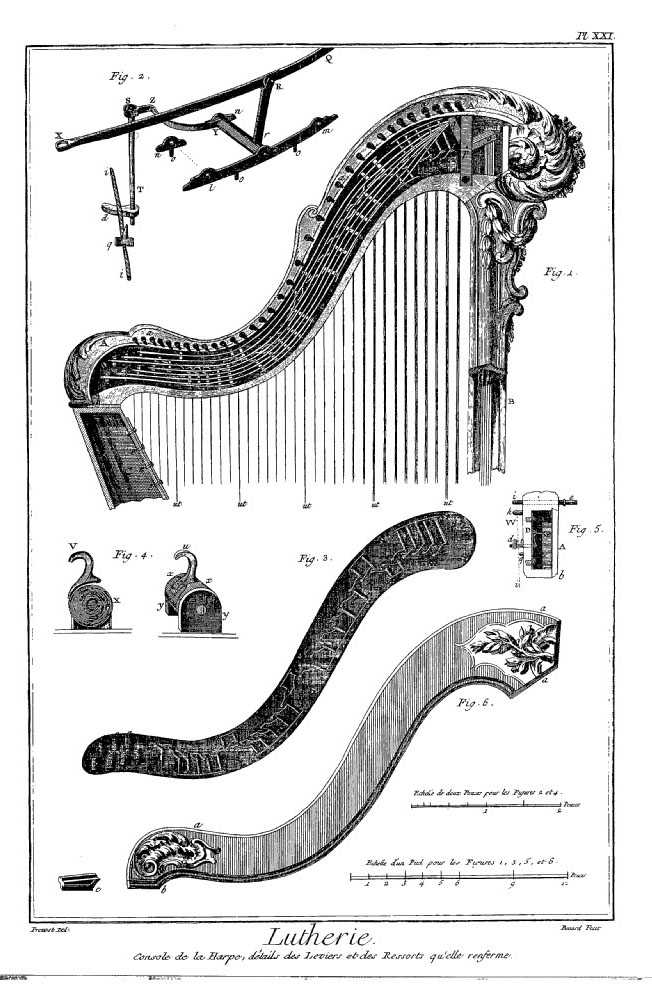

The introduction of pedals changed the form of the harp. Because the harp column housed the mechanism connecting the pedals to the strings, it had to be straight and hollow. The now easily-recognizable harp shape, with a curved shoulder and tall neck, was established with this new design. In 18th century paintings, including a self-portrait by Rose Adélaïde Ducreux, this part of the harp was all that had to be represented in order to signify the instrument’s presence, and thus its symbolic connotations.

Exterior surface design

Harps were decorated in keeping with trends in furniture design. Almost always placed at the top of the neck was a swirling scroll, a typical Rococo ornament. During the Neoclassical era and lasting into Napoleon’s regime, the scroll was replaced with a classical column—unlike the harpsichord, the harp survived as a fashionable instrument through the French Revolution.

Gilt wood in patterns of acanthus leaves and painted soundboards with floral and pastoral scenes dominated harp decoration, in the spirit of Rousseau’s “back to nature” ideal. The extravagance of most surviving 18th century harps appears to be fit for royalty, but those made for Queen Marie Antoinette were especially sumptuous.