The Oeben Mechanical Table as a Symbol of Globalism, Individualism and Opulence

The type of ornamental and mechanical attention, as seen in the Oeben Mechanical Table, was made possible by the rehabilitation of French consumerism. As the consumers paid increasing attention to luxury, the demand for extravagant furniture bred a distinct style. Emphasis now was on furnishings that could speak towards the refined taste of their owners all while maintaining an elegant air of multi-purposed functionality and personal comfort.

– – –

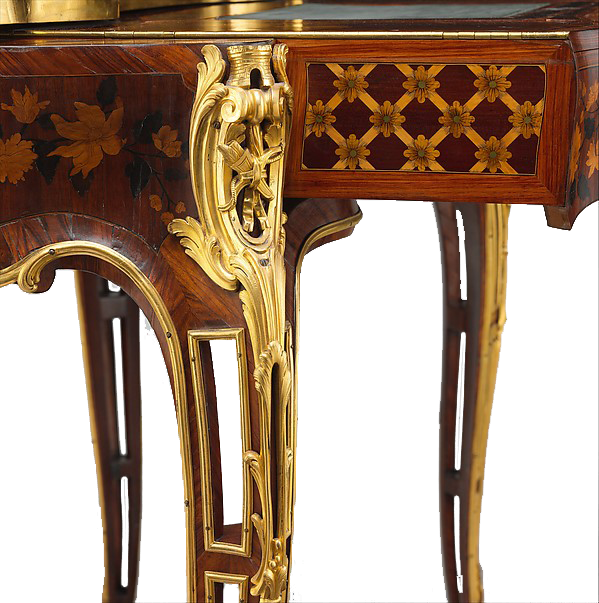

The Oeben Table does just this, created by Jean- François Oeben a furniture maker well known for his incredibly elaborate mechanical tables, the desk’s detailed legwork, naturalistic floral marquetry and complex interior mechanisms all lend themselves to the royal narrative for which the desk was intended to inhabit.

– – –

This period of ostentatious behavior and expenditures was also marked by a desire for privacy and individualism. “The desk”, a highly personalized place to articulate ideas, represents freedom of thought and expression. The Oeben Table’s transparent representation of privacy is confused by it’s gaudy ornamentation. Although one’s privacy is preserved within the desk, the security of free thought is celebrated in a mockingly flamboyant way.

The Oeben Mechanical Table (multiple views), Jean François Oeben (1721-1763 and Roger Vandercruse (1727-1799), ca. 1761-63, French, Oak veneered with various other woods, Metalwork of Gold, Copper and Bronze, 69.9 × 81.9 × 46.7 cm, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982. and the Claude Perron (master 1750, died in or before 1777), 1763–64, French, Paris, Gold, enamel, 1 9/16 x 3 5/16 x 2 1/2 in. (4 x 8.4 x 6.4cm), Metalwork-Gold and Platinum, Bequest of Catherine D. Wentworth, 1948, 48.187.450, On view at The Met Fifth Avenue

The Role of Trade, Empire and Ideology in the Development of French Material Culture as Seen Through The Oeben Mechanical Table

The Enlightenment’s re-prioritization of ideals along with a newly globalized Western world transformed the French economy and style. Many materials such as wood, silver, gold and porcelain, all of which were crucial elements to 18th century furnishings, made their way to Paris through the Second Atlantic trade system. State-chartered trading companies established commercial networks linking West Africa, the Caribbean region, and the Americas. With this colonial expansion, Europe generated unprecedented profits through the circulation of manufactured European goods, African slaves, and New World luxury commodities facilitated by slave-labour production.

– – –

As the networks of trade and empire became more established, those commodities became more available; demand easily met supply as the exotic commodities soon became synonymous with the conveyance of wealth. It was through this network that French merchants found themselves routinely in the Caribbean, Brazil and the Americas, building up new world empires for the continued extraction of raw materials to satiate a changing French material culture infatuated with exoticism. This provides something as simple as a writing desk with a complex global fingerprint.

– – –

French furniture had gradually undergone changes until Louis XIV developed a uniquely French form of grandeur; a time of ornate and lavish furniture for elegant environments. He has been credited with defining the distinct opulence of this aesthetic; an aesthetic so powerful that it continues to be replicated today. So although it is seemingly congruous to view French furniture as a product of a uniquely French framework, given the global evolution of European material culture, this is an inaccurate assumption. The Oeben Mechanical Table allows us to formalize this concept and instead place French furniture within the global cultural system generated by cross Atlantic trade as visualized below.

For more information on the interior mechanics and exterior surface design of similar mechanical tables, see this Virtual Enlightenment page.

Click below to find out more about the materials that make up this table:

The Oeben Mechanical Table (detail shot), Jean François Oeben (1721-1763 and Roger Vandercruse (1727-1799), ca. 1761-63, French, Oak veneered with various other woods, Metalwork of Gold, Copper and Bronze, 69.9 × 81.9 × 46.7 cm, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982. and the Claude Perron (master 1750, died in or before 1777), 1763–64, French, Paris, Gold, enamel, 1 9/16 x 3 5/16 x 2 1/2 in. (4 x 8.4 x 6.4cm), Metalwork-Gold and Platinum, Bequest of Catherine D. Wentworth, 1948, 48.187.450, On view at The Met Fifth Avenue