Interior Mechanics

What hidden structures lie within?

Mechanical Desks

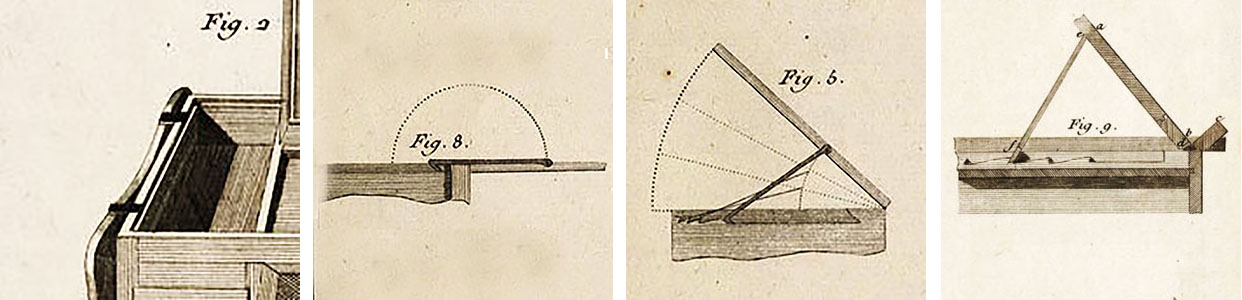

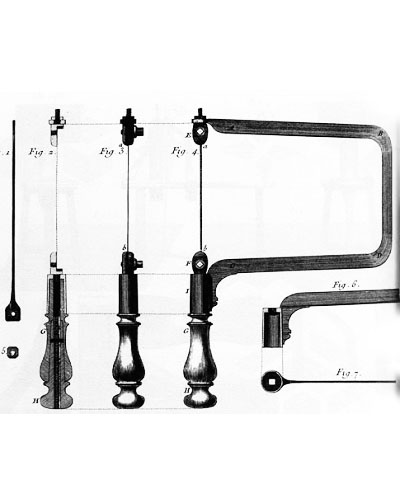

The mechanical structure inside writing desks demonstrated both sophistication and a desire for discretion. When closed, writing desks appear to be completely normal tables. However, they unfolded into spectacles. The mechanical skeleton was able to perform amazing tasks, but was almost entirely hidden beneath the furniture’s veneer, to retain the desk’s beauty and mystery.

Secret Functions

Desks were designed such that owners, who had learned how they worked, could operate them discreetly. In these Riesener desks, a series of small buttons are placed along the panel which face the desk user. Pushing them causes loaded springs to swing open drawers on carefully crafted hinges. These parts of the desk surface which might appear to be purely decorative, would reveal themselves to be functional cavities for the storage of personal objects.

Desks, designed for women, could create an air of seduction, mystery, and refined privacy. If the desk was used as part of the daily grooming ritual of the toilette, to which a woman could invite her romantic or sexual interest, she would be able to operate the desk using small and elegant gestures. If used as a writing desk in complete privacy, a woman could ensure that her most precious and personal belongings were kept in the most difficult to access drawers. Protected by mechanics under the guise of magic, a woman could use the table as a means of self-fashioning.

Mechanical ingenuity combined with multiple purposes led to the development of some highly-customized pieces. The Tessé Room desk was made while Queen Marie Antoinette of France, who commissioned it, was pregnant. Because she would become very uncomfortable after sitting for too long, the desk was fitted, by the mécanicien de la reine Jean-Gotfritt Mercklein, with a crank which allowed its tabletop to slide up metal rods running through the desk’s hollow legs, so that she could use it while standing. The desk’s central panel can be raised as a lectern for reading and writing or flipped to reveal a mirror.

The Body as a Machine

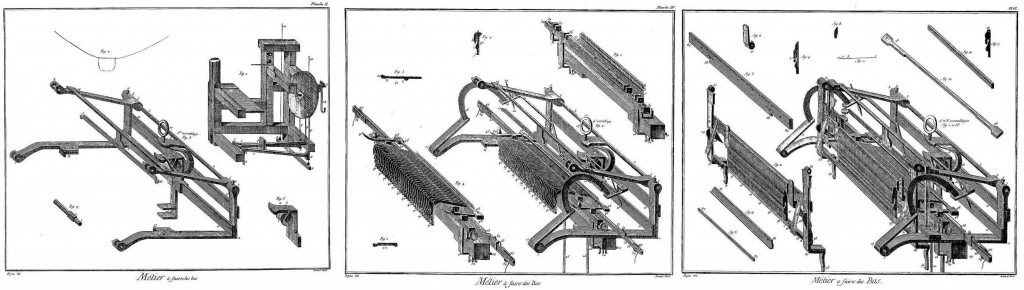

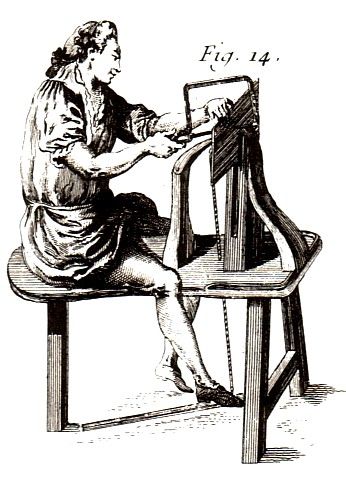

Diderot’s Encyclopédie demonstrated a fascination for demystifying and making known the processes behind how objects were made. A machine for creating les bas, or undergarments, was rendered in six detailed etchings, demonstrating how its separate pieces functioned together, demonstrating how even the creation of something lowly and unseen, like undergarments, was the result of incredible mechanics.

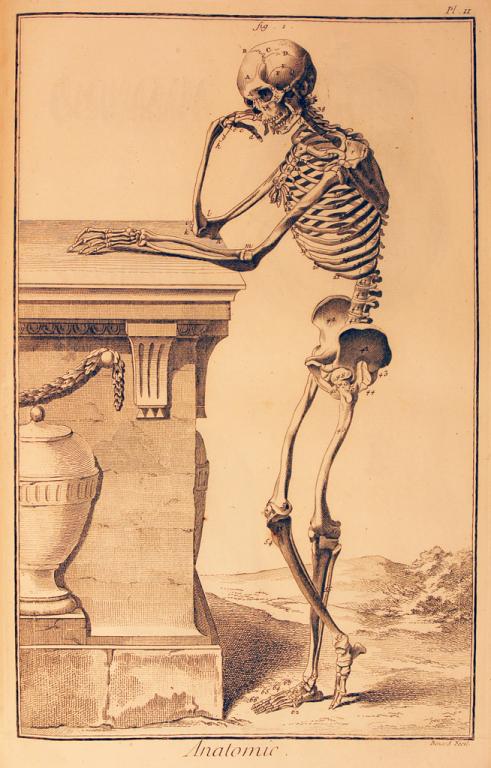

Meticulous etchings of the human skeletal structure can be found in in Diderot’s Encyclopédie. Similarly, Julian Offray de la Mettrie, a physician and philosopher, published Homme Machine (Man, A Machine) in 1748 which argued for the inherently mechanical nature of the human body. Writing of the ‘springs of the human machine,’ he notes, for example, how “the body draws back, struck with terror at the sight of an unexpected precipice, the eyelids blink under the threat of a blow.”

The Enlightenment shift towards thinking about people and furniture in mechanical terms demonstrates the effect of developing technology. This attitude produced spaces for the development of the private self and inspired deep investigation into the true form of all things.

–

Exterior Surface Design

What makes the writing desk’s surface so complex?

The outside of the writing desk serves as a canvas on which the ébéniste (furniture-maker) could display his supreme taste and artistic skill. The veneer is where the desk must entertain the eyes of viewers and users. Like the hidden mechanical structure which lies underneath, the veneer is meant to amaze and mystify anyone who looks at it–how is it that wood and gold can be manipulated into miniature paintings and sculptures? The challenge was to find a balance between the form of the surface and function of the object, while realizing the decorative potential of both.

Wood Marquetry

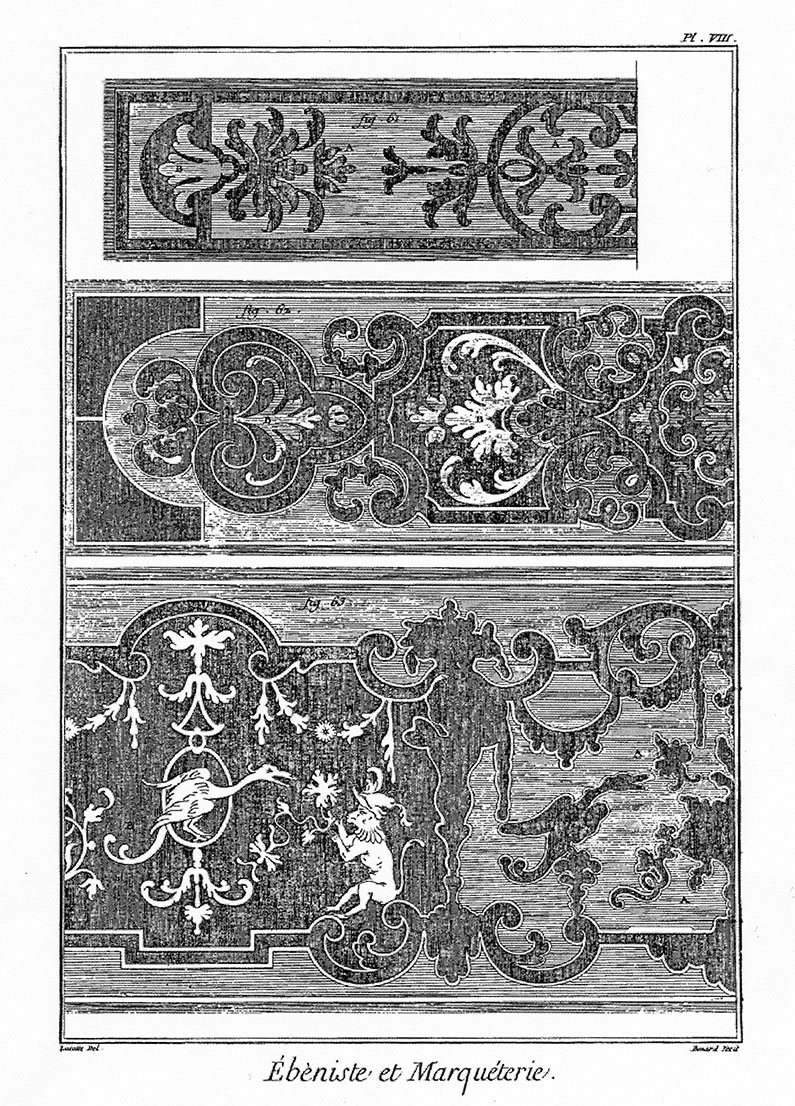

Marquetry is the practice by which furniture-makers create designs on the veneers of their furniture using thin pieces of wood which are carefully cut, dyed, and inlaid onto the furniture’s surface. By the late eighteenth-century, techniques and tastes in wood marquetry had undergone extreme refinement, allowing the desk-maker Riesener to use quite a very sophisticated technique. This process is called ‘advanced inlay.’

To make a floral pattern, for instance, each flower would have to be inserted into a cavity in the veneer of the furniture. After gluing a piece of background veneer to a finished furniture carcass, a marqueteur would draw, then mark out with a scriber, and finally deeply cut into the background veneer with an inlay knife to create the cavity into which to inlay the design. Once completed, the veneer would be sanded down, if necessary, and a finish would be applied.

Because advanced inlay allowed for the creation of virtually any design, wood marquetry produced rich and vibrant images. However, many marqueteurs used organic dyes for the patterns of their work, so the rich contrasts and original colors have faded significantly over time. Often, ébénistes had signature patterns they would reuse. Riesener, for instance, often used the grill and water-lily pattern seen on the two Marie Antoinette desks in the Met’s collection.

Faded marquetry pattern (right) can be seen in its original colors (left) when restored in Photoshop

Gilt Bronze

Gilt bronze elements also provided richness to the veneer of fine furniture. However, unlike wood marquetry, gilt bronze also served essential utilitarian purposes, especially on writing desks. To learn more about this material in general and the many ways it was used, visit the gilt bronze page.

Writing desks were designed to be light and movable, so that one could choose where in the home to write. This made them very vulnerable to being bumped against other pieces of furniture, or getting otherwise damaged or run down over time. Gilt bronze mounts were attached to vulnerable areas using drills through the wood like a suit of armor protecting the body’s major organs. Like armor, gilt-bronze protection could be quite ornate.

Gilt-bronze was also fitted over keyholes to keep the wood from becoming nicked during locking and unlocking. Because they were private objects, writing desks necessitated locks and keys to function properly. Paradoxically, gilt bronze at once concealed and brought attention to a desk’s secrets.