Painting of a woman at her toilette, wearing a stay, called “A Lady Showing a Bracelet to Her Suitor” by Jean François de Troy (1734)

Eighteenth-century stays were worn under women’s clothes and would not be visible, but were still finely crafted. They were different from nineteenth-century corsets in that they were constructed using whalebone (baleen) in place of metal, and were meant to hold a woman’s shape in a curvilinear line, rather than transform it by making the waist smaller. Stays supported the woman’s body from the waist up, to help strengthen the core. Originally, stays were not uncomfortable, but instead their design was meant to allow for reclining in cushioned chairs. They helped improve posture by keeping the torso upright, but were not as constricting as the metal corsets used later.

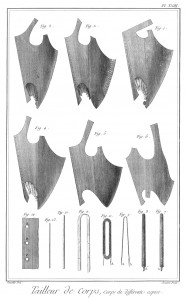

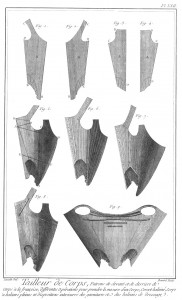

Encyclopédie plate with example of how whalebone reinforcements were added to the top of the stay. Fig. 5 shows measurements in stay-making to fit a specific woman’s body

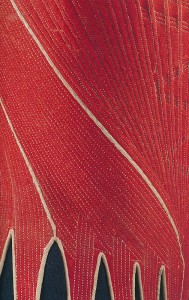

The stay-making process was labor intensive and performed by men, despite stays being women’s wear. It was believed that women’s hands were too delicate and weak to perform the cutting and construction needed to work the materials used. The form of the stay was created from three layers of fabric, with wool on the outside as a “facing fabric,” baleen, linen or canvas behind the whalebone, and linen lining on the inside. Additional whalebone was sometimes used in the top of the stay, shaping the wearer’s bust (placement can be seen in Fig. 9 of the Encyclopédie plate above). The baleen was retrieved from the Right Atlantic Whale’s mouth, and was desired for its malleable qualities. It was strong, flexible, and easy to cut. Even when cut (different bone sizes shown in other plate fig. 12 and 13 of the plate below), the baleen remained sturdy.

The half-boned stay (Fig. 6 below) was most popular in the end of the eighteenth-century. Stays were constructed in ten sections, and often were colorful with white stitching and seams, drawing attention to the craftsmanship and the placement of the whalebone, and highlighting their elegant shape. The flaps at the base of a stay made women’s petticoats look fuller when tied over them. Stays also allowed movement to be unconstrained, so a woman could bend while maintaining good posture. Each stay was made to fit a specific woman’s measurements, as seen in Fig. 5 of the plate above.

For more information on stays, please see:

Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeeh and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 1998.

Starobinski, Jean, Philippe Duboy, Akiko Fukai, Jun I. Kanai, Toshio Horii, Janet Arnold, and Martin Kamer. Revolution in Fashion 1715-1815. Edited by Amy Handy. New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.

Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/C.I.50.8.2

Image citations:

Diderot, Denis, and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert. Encyclopédie Ou Dictionnaire Raisonné Des Sciences, Des Arts et Des Métiers. Geneve: J.L. Pellet; [etc.], 1778.

Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeeh and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 1998.

Higonnet, Anne. “Textiles & Clothing.” Barnard College. Diana Center, New York, NY. 30 March 2015. Lecture.

Starobinski, Jean, Philippe Duboy, Akiko Fukai, Jun I. Kanai, Toshio Horii, Janet Arnold, and Martin Kamer. Revolution in Fashion 1715-1815. Edited by Amy Handy. New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.