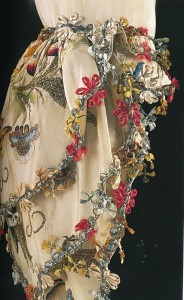

In women’s wear, tassels were used to decorate the front panels or bottoms of skirts (as seen in the Rose Ducreux self-portrait, above), and for men, they adorned cuffs, pockets, coat fronts, lapels, and pleats on the coat backs. The materials used to make tassels were meant to look fluffy, shiny, and delicate. Some were made of chenille (a velvety silk cord) that could be braided. Others incorporated showy, silver spangles, as seen below. Spangled tassels were particularly flashy, and were meant to charm and impress women when worn on the cuff’s a man’s coat. They swung when the man moved his arm, catching candle light in an indoor setting, and shimmering in the dark.

Man’s wool coat with silver and silver-gilt, spangled tassels

Tassels were a type of “narrow ware,” along with many other decorative elements of clothing, including ribbons, fringes, and braids. The name came from the “narrow-hand loom” originally used by women in the 1300s-1400s to make ribbon. Its output was slow, only allowing for one ribbon to be created at a time. The invention of the “Dutch engine loom” in the 1600s allowed for a higher output of ribbon. One loom operator could produce 24 ribbons at once, greatly increasing the speed of production, and possibly contributing to the popularity of these adornments beginning in the seventeenth-century and continuing for many more. By the end of the seventeenth-century, the trimmings of clothing became more costly than the fabrics themselves. The trim was a very important aspect of an outfit—sometimes trimmings were replaced on the same dress to change the wearer’s look.

Embroidered silk gown with metal threads. This is an example of fly fringe trimming

In addition to tassels, other decorations also were used around sleeves, including “fly fringe trimming” of multicolored rosettes, which often matched embroidered designs in the cloth. To further compliment fringes, fabric could be draped to form flowers, ruffles, and pleats. Ribbon bows could be buttoned to all portions of outfits. Other ribbons were used along with jewels and pearls to adorn women’s hair, as seen in the portrait of Rose Ducreux. The ribbon, of course, matched the color and style of the outfit, and was sometimes even present in gloves. Ribbons or lace, sometimes combined with jewels, made necklaces and additional accessories. A popular style after the French Revolution was to wear miniature guillotines as pendants, or thin red ribbons around one’s neck, mimicking the chopping off of heads. Unfortunately, many ribbons were delicately made, and have not survived into the present day.

For more information on tassels, please see:

Delpierre, Madeleine. Dress in France in the Eighteenth Century. Translated by Caroline Beamish. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997.

Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeeh and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 1998.

Starobinski, Jean, Philippe Duboy, Akiko Fukai, Jun I. Kanai, Toshio Horii, Janet Arnold, and Martin Kamer. Revolution in Fashion 1715-1815. Edited by Amy Handy. New York: Abbeville Press, 1989.

Image citations:

Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeeh and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 1998.

“Rose-Adélaïde Ducreux: Self-Portrait with a Harp (67.55.1)”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/67.55.1 (December 2013).