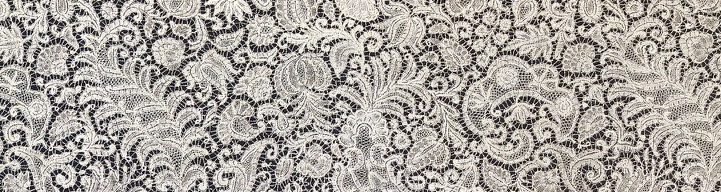

The lace-making process was long and difficult, making lace one of the most expensive clothing decorations in the eighteenth-century. It was greatly valued, and carefully cared for by its owners. It had a variety of uses in clothing, including being used as trim on women’s jackets, sleeves, and around their necks. Lace was displayed with pride, and highlighted a person’s wealth.

People loved the lightness and delicate appearance of lace. There were different qualities of lace, with more fine designs being the most expensive and difficult to produce. Lace making originally took off in Venice, Italy, but to keep business from leaving France, the government organized and supported workshops in specific towns. A desire for French products, such as lace, to be the best in Europe fueled a sense of nationalism. The French lace designs differed from those of Venice in being flatter, with less texture and defined edges. Lace making took up the new concept of the assembly-line, moving away from the previous method of craft-making that was required in guilds, which involved one individual creating objects from beginning to end.

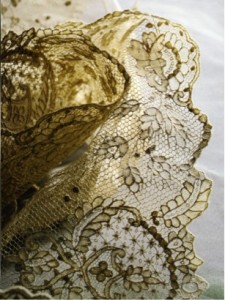

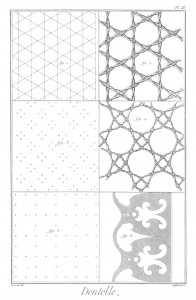

During the eighteenth century, the process of making lace involved wrapping linen around single horsehairs, though this is no longer performed. This fine, needle lace was made in Alençon, France, and a museum still exists there today. Needle lace was thicker, and usually worn in the winter months. The finer the lace, the more it cost. At a maximum, each lace maker could produce only three square centimeters per day, making the process very time and labor intensive. Many portraits (examples below) displayed lace. The painting of Madame de Pompadour below shows eight ruffles on her arm, drawing attention to her wealth and associated power and status. An alternative type of lace was called “bobbin lace,” which was made on a pillow using pins to poke out a design in fabric, and then drawing over the holes with thread attached to bobbins or bones. Bobbin lace was produced in Valenciennes, France, and was generally worn in the summer due to its lightness. Workers in Valenciennes had to work in special cellars to keep threads at the correct humidity. Many other lace makers could work from home.

Encyclopédie plate of pin hole patterns for bobbin lace on left, and intricate lace designs on right

The presence of lace would be highlighted by a person’s movements. For example, when removing a shimmering snuffbox from one’s pocket, the lace on one’s arm would be exaggerated. In fact, any movement of the arm would draw attention to lace. In the portrait of Rose Ducreux, below, the artist’s arm would move as she played the harp, highlighting the valuable materials she wore on her sleeve. Additionally, multiple layers of lace would create interesting patterns as light shone through them. The aesthetic beauty of the material and the knowledge of the labor that went into making it made lace a luxury good in eighteenth-century France. It remained an important indicator of class and wealth throughout the century.

.

For more information on lace, please see:

Bremer-David, Charissa, ed. Paris : Life & Luxury in the Eighteenth Century. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.