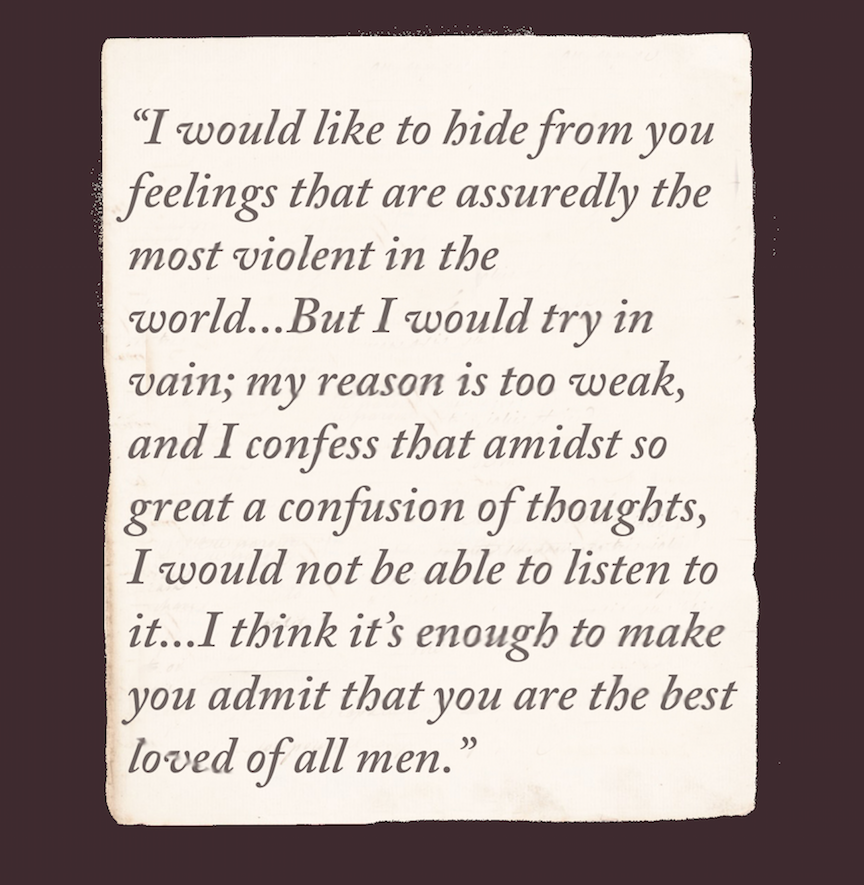

Excerpt of a love letter imposed onto paper from an eighteenth-century letter at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Accession Number 1985.151.1a). Composite image by Emma Snover.

Above is an excerpt from Marie-Catherine Desjardins’ passionate love letter to Antoine de Villedieu (Jensen 45). As literacy rates improved in the eighteenth-century, elite women participated more in the written arts, particularly in the genre of love letters (Goodman 2). Eighteenth-century paintings reveal the rise of this genre, depicting letter-writing as an elite activity of leisure for women. Love letters functioned as intimate products of romantic pursuits in a relationship best described as “galanterie,” the transcendence of physical desire through a spiritual connection (Jensen 4).

Watch the video below to see the activity of letter writing in eighteenth-century lighting and dress conditions, then continue reading the page to learn more about the details of this activity.

This video re-enacts Madame de Pompadour writing a love letter in candlelight. The text derives from Marie-Catherine Desjardins’ letter to Antoine de Villedieu. It took four candles to provide sufficient light to write the letter, illuminating the lighting circumstances of the Enlightenment. The sleeve on the woman’s arm reveals the translucency of intricate lace in candlelight. The video emphasizes the details surrounding the activity of letter writing. Video by Alex Bass, Emma Snover, and Constance Zhou.

Before beginning a letter, a woman’s table would have to be opened to the right surface for this activity (an action likely performed by a servant). The video below shows the Oeben table open to reveal the writing surface.

This video shows the Oeben mechanical table sliding open to reveal a writing function, followed by an eighteenth-century falling onto the table. The video demonstrates the working of mechanical functions and underscores the hidden layers of the table that contribute to its private intrigue. Video by Emma Snover.

Click on different areas of the desk below to learn more about the tools that contributed to the writing function.

Annotated image of the eighteenth-century letter and an étui placed at Oeben’s mechanical table. This image demonstrates how the table would appear with accessories used for letter writing. Image by Emma Snover.

The rise of letter writing for women coincided with the consumerism of the Enlightenment. The étui, inkwell, and stationary needed for letter writing validates the notion that “objects were not simply owned, but performed” (Hellman 417). These luxurious products were designed for epistolary use at a private table. Elite women would seek the most precious of objects to undertake this intimate activity. Some inkwells were even heart-shaped (Goodman 181), demonstrating a relationship between a woman’s written word and love.

Though by its nature a love letter encourages a receiver, the activity developed as “an everyday privileged site for the expression of the self” (Grassi, Goodman, 3). The rise of the private interior throughout the Enlightenment invited this private activity, and empowered a woman’s individualism. Celebrating this privilege, some writing desks were even classified as bonheur-du-jour, or happiness of the day, denoting the pleasure women experienced in writing their letters (Kisluk-Grosheide 2006, 14).

Continue here to finish the story.

Pages

practice